Featured Collections

- Museum Collections

- View All Images

- 20th Century

- 19th Century

- 18th Century

- 17th Century

- Baroque

- Renaissance

- Medieval

- Special Collections

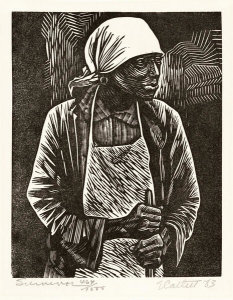

- African American Artists

- Women Artists

- Works on Paper

- American Art

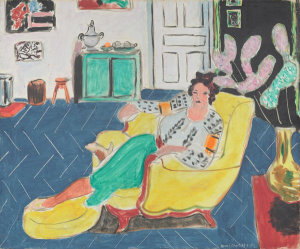

- European Art

- Old Masters

- Popular Movements

- Impressionism

- Post-Impressionism

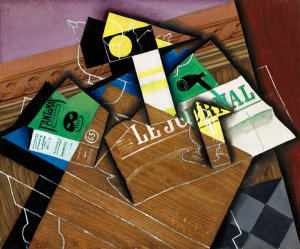

- Modernism

- Romanticism

- Special Exhibitions

- Mary Cassatt: An American in Paris

- The Stars We Do Not See: Australian Indigenous Art

Individually made-to-order for shipping within 10 business days

Artists

- Renaissance & Baroque

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Jan van Eyck

- Raphael

- El Greco

- Johannes Vermeer

- Jan Davisz de Heem

- Rembrandt van Rijn

Your Custom Prints order supports the National Gallery of Art

Subjects

- Landscapes

- All Landscapes

- Countryside

- Mountains

- Sunsets and Sunrises

- Still Life

- All Still Life

- Cuisine

- Floral

- Waterscapes

- All Waterscapes

- Harbors

- Ocean

- Rivers

- Waterfalls

- Religion and Spirituality

- Christianity

- Judaism

- Other Featured Subjects

- Abstract

- Animals

- Architecture

- Cuisine

- Flowers and Plants

- Portraits

- Boats and Ships

Prints and framing handmade to order in the USA

Top Sellers

- Edward Hopper, Ground Swell

- Henri Matisse, Open Window, Collioure

- Claude Monet, Woman with a Parasol

- Vincent van Gogh, Green Wheat Fields

- Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Young Girl Reading

- Vincent van Gogh, Roses

- Claude Monet, The Japanese Footbridge

- Claude Monet, The Artist's Garden in Argenteuil

- Thomas Cole, The Voyage of Life: Childhood

- Mark Rothko, Untitled

- Thomas Cole, The Voyage of Life: Manhood

- Henri Matisse, Woman with Amphora and Pomegranates

- Jan Davisz de Heem, Vase of Flowers, c. 1660

- Thomas Cole, The Voyage of Life: Youth

- Leonardo da Vinci, Ginevra de' Benci

- Auguste Renoir, Pont Neuf, Paris

- Johannes Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance

- Claude Monet, The Bridge at Argenteuil

- Albert Bierstadt, The Last of the Buffalo

- Albert Bierstadt, Mount Corcoran

Could any of these be your choices too?